____________________________________________

|

| Quarterfinal 1 Winner |

Dellinger on Freedom:

But on the whole, [Freedom's] writing is deep and rich and steady. The themes are familiar yet surprisingly well-woven. The characters and their interactions are finely observed, high-resolution, and intricately textured. By the time I was two-thirds of the way through, references to moments and people from earlier in the book brought back what felt like actual memories. Freedom is a very, very long page-turner, written by a grownup.

While I agree with Dellinger's end assessment, "written by a grownup" is a devastating indictment of Room. The charitable reading of this is that Dellinger is referring to the voice of the narrator of Room and not to the writer herself, but that's not what the sentence suggests. The question it raises, though, is an interesting one: is a first-person book about a five-year old written, in essence, by that five-year old? What depth and complexity can an author layer on top of such a limitation? I do think that Donogue's choice of perspective absolves her of the responsibility to add complexity, but is that to the good of the work? Some might argue that writing a compelling narrative through the eyes of a five-year old adds difficulty, but it seems to me that it actually lowers the overall degree of difficulty, since nettlesome, adult concerns and ideas are foreclosed. Hence, Room is a tighter narrative, but it's just so infuriatingly narrow. Donogue doesn't give us the most interesting part of the story---the interior world of a woman who has been raped every day for years and raised a son in a ten-by-ten shed. I think this point goes for almost all stories written from a child's point-of-view; they must be penalized in the final judgment for not dealing with the full force of adult consciousness.

|

| Quarterfinal 2 Winner |

Batumann on A Visit from the Goon Squad:

"...as for A Visit From the Goon Squad—interconnected, chronologically-scrambled short stories with recurring characters—I’d heard it described as “a display of Ms. Egan’s extreme virtuosity.” The word “virtuosity,” in book reviews, is a real red flag for me. Perhaps relatedly, I’m suspicious of interconnected stories, which often remind me of the arbitrary, contrived tendency of literature, the tendency that poses a particular threat to the short story, a form where characters all too easily become interchangeable, and each plot seems like it might as well be a sequel or prequel to the one before.

I wish Batumann would have explained "the word 'virtuosity,' in book reviews, is a real red flag for me." My guess is that she sees 'virtuosity' as a privileging of form over content. I find myself increasingly sympathetic to this reading. Goon Squad is remarkably well-executed, with formal dexterity that serves the work's rich intellectual and emotional concerns. I've noticed a rise of late of what I've begun to think of as "balloon-animal fiction"--fiction that pairs undeniable writerly gifts with otherwise unremarkable substance.

It is a neat trick to make a balloon that looks like a dog--but the likeness of the dog is still fairly crude. If the goal is to make a likeness of a dog, then even the most adroit balloon-savant will lose to the average practitioner of most standard media. In art, sometimes we over-value balloon-twisting ability, to the detriment of our understanding of dogs.

(I am thinking here of Swamplandia!, The Education of Bruno Littlemore, The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake, Room, and to a lesser extent The Fates Will Find Their Way). I think there's more to be said about this, but that's as far as I've wandered to this point.

|

| Quarterfinal 3 Winner |

Williams on Nox:

O’Rourke [reviewer for The New York Times -RA] strains to give voice where [Nox] is silent, an effort I found almost impossible to mount myself. Carson’s loss must have been profound, and Nox’s profundity is meant to arise from the gap between her almost illusory relationship with her brother and her real suffering. The fact that she has a far more intimate knowledge of Herodotus and Catullus than she does of her brother might strike some as interesting, even moving. I just found it distant and cold.

O’Rourke [reviewer for The New York Times -RA] strains to give voice where [Nox] is silent, an effort I found almost impossible to mount myself. Carson’s loss must have been profound, and Nox’s profundity is meant to arise from the gap between her almost illusory relationship with her brother and her real suffering. The fact that she has a far more intimate knowledge of Herodotus and Catullus than she does of her brother might strike some as interesting, even moving. I just found it distant and cold.

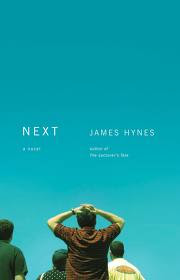

I think Williams is right on here, though I would have come to a different judgment, as I am one of those who, as Williams posits, found Carson's "far more intimate knowledge of Herodotus and Catullus" than her knowledge of her brother "moving." I see Carson' grief as a scholar or writer's lament--her immersion into a literary/artistic/historical worlds supersedes her participation in the imminent world. This is compounded by the fact that her only recourse for this division is more literature, more history, more art. Nox is a bandage on an open-wound. Hynes must deploy considerable artifice, as Williams notes, to generate what pathos there is to be found in Next; I'll take inscrutability and distance over construction and spectacle.

|

| Quarterfinal 4 Winner |

Ortega on The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake:

The book carried me back to my embarrassing teenage days, while also raising the stakes. Rose knows she is different and yearns to fit in, just like I did and just like all teenagers do. But she is different for reasons that put to shame the normal teenage feelings of being an outsider. She would have rejoiced if her only “difference” had been a naggy brother. In the end, her story brings with it a reminder that the individual things that make every family special go far beyond bed sheets.

Bender's book does indeed replicate and intensify the central solipsism of teenager-hood: "Rose knows she is different and yearns to fit in, just like I did and just like all teenagers do." But replication and intensification are not of and in themselves avenues toward understanding. Ortega's favorable judgment of The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake seems to hinge on the novel's ability to "carry [her] back to [her] embarrassing teenage days," but she does not explain why such a transportation is valuable and/or entertaining. Instead, she says that the "story brings with it a reminder that the individual things that make every family special go far beyond the bed sheets." I don't know what this means. Does she think that recognizing familial individuation might make us think of our own families differently? Or that the deep structure of family systems varies somehow and we should acknowledge that? That is it is a "reminder" suggests that we have forgotten something, though I have a hard time imagining a reasonable person believing all families are pretty much the same (though this even this logic is contradicted by the statement that all teenagers are the same.)

_______________

On that cranky note, we sail into the semi-finals. Now is time for the favorites to collide and for zombies to rise. The two favorites have steam-rolled into an epic showdown, and while Skippy might be dead, my guess is that Murray's book is laying in the tall grass.

_______________

Until April 15th, all referral fees generated by The Reading Ape will go to support Rock City Books & Coffee. Read more about the effort here. Just click through any of the below to do your shopping, and you'll be helping. Many thanks.